When the Netherlands still watched TV broadcasts in black and white, Johan Cruyff already came to the realization that he represented a special value as a top footballer. And how he could best capitalize on that. At a young age, Cruyff developed an unmistakable love for money. The later Ajax chairman Ton Harmsen even called Cruyff a ‘money wolf’.

It is the year 1968 and it seems that the revolution has broken out everywhere. In many cities around the world, young people are rebelling against the ruling authorities. In America, large-scale demonstrations are taking place against the war in Vietnam. However, in the then West German capital Bonn tens of thousands of students take to the streets after the murder of the left-wing student leader Rudi Dutschke. And in Paris, the student uprising even culminates in a general strike that shuts down all of France for days.

The students turn with their violent protests against the established order, both in education and in politics. They find them conservative and authoritarian, and are becoming increasingly distant from their own world of experience. They argue for a new education system, for free love and for anarchy. Or a society without higher, guiding power.

Obviously, that guiding power did not like that. Because of his leading role in the uprising, the revolutionary Daniel Cohn-Bendit is brought to justice in Paris. Almost at the same time, another sensational lawsuit is being filed in Amsterdam: Johan Cruyff versus Cor du Buy Sport NV.

This is Part 6 of #TheCruyffStory. Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, part 5.

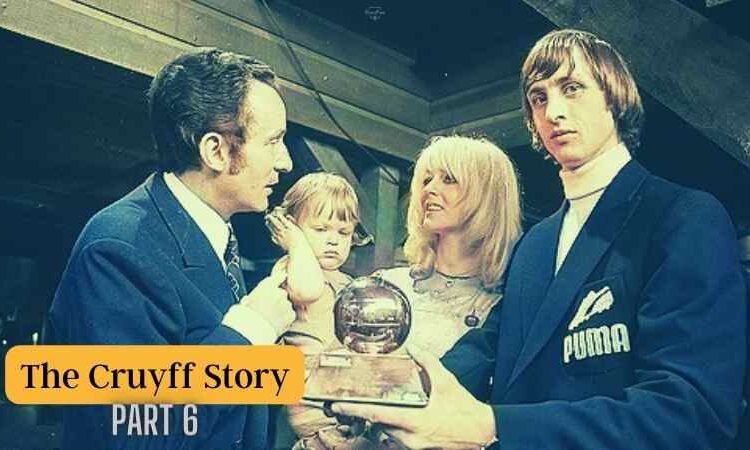

The then 21-year-old Cruyff has already become top scorer of the Dutch Eredivisie a season earlier. Cor du Buy is a former table tennis player whose sports equipment company wants to make good use of the star-in-the-making. A contract with mother Cruyff was agreed in 1967. This provides that Johan will play football on Puma shoes for 1,500 guilders a year and gives Du Buy the exclusive right to market shoes and tracksuits under the name Cruijffie. For every pair sold, Cruyff touches another 1.75 guilders.

But Cruyff has refused to play on Pumas for more than half a year already, because they destroy his already fragile ankles, he claims. Du Buy is demanding 24,500 guilders as compensation for that breach of contract and has Cruyff’s income seized. On Tuesday, September 3, 1968, the opponents faced each other in court.

A man of principles

In retrospect, the trial tells the life story of Cruyff. Although still young, he does not walk away from the conflict. The star himself is not present in court, because he has been called up for the Dutch national team. Rinus Michels plays an important role in the argument of Cruyff’s lawyer, because the Ajax coach has forbidden Cruyff to play football on Puma shoes. According to Du Buy, Puma can tailor any shoe you want, but Cruyff simply does not have time for fitting sessions. Court president Mr. Ubbo Stheeman, in turn, expresses doubts about the pinching ankles and suggests that the footballer is mainly looking for more money. ‘Then he probably wants to wear those shoes.’

How providential. The judge ruled in favor of Cor du Buy, but as if nothing had happened at all, the dispute between Du Buy and Cruyff is settled. In fact, yesterday’s enemies even sign a new contract for tomorrow. The footballer continues to play at Puma-shoes and receives no less than 25 thousand guilders per year. Once again it turns out: not the fight, but the outcome is important.

A lesson for life

Johan Cruyff learned that wisdom early on. As a teenager still fighting against the pimples in the face, he is already fighting adult board members. In the early sixties, Cruyff has a youth contract with Ajax that earns him fifty guilders a week. The moment he has to participate in the second team, his fellow players do receive match premiums, but Cruyff does not because he has a weekly contract. Certainly not for the last time he will seek redress from the club management. And – certainly not for the last time – they think he’s just a cheeky little guy.

That is partly due to his use of language, as Cruyff will tell later. ‘They made the comparison with an apprentice salesman in a store who has yet to learn the trade. I didn’t have to whine, that’s what it came down to. Then I replied that an apprentice salesperson who does the work of an adult salesperson should also be rewarded equally. It’s not about age, but about the contribution you make. People need to get what they are entitled to. Looking back, that has been an important change: the rights of footballers have improved enormously.’

The player is the ‘Show’

An important reference date is 13 June 1967. On that day, Johan Cruyff meets his love Danny, the daughter of Amsterdam businessman Cor Coster, at the wedding of teammate Piet Keizer. The two married on December 2, 1968 and Cruyff not only got a father-in-law, but also an agent.

Until then, the confident Cruyff has looked after his own affairs, possibly assisted by his mother. He arranges his first professional contract with Ajax himself, for fifteen thousand guilders per season. However, Coster, a dealer in gold, watches and jewelry, believes that Cruyff has let himself be wrapped up by Ajax. He speaks openly of a bad contract and believes that his new son-in-law is not at home in the world of business.

At the same time, Coster sees the unprecedented possibilities of the footballer Cruyff, who, according to him, just like George Best and Günter Netzer, has the potential to grow into an icon of a generation. And that means a commercial value that goes far beyond the outcome of a match or the ranking on a top scorer list. ‘Cruyff is an article in my eyes’, says Coster and what we nowadays find quite normal with world stars such as Cristiano Ronald and Lionel Messi, is then set in motion: the commercial exploitation of a top footballer.

PR is Important

The ‘businesslike relief of his son-in-law’, as Coster calls his interferences, does Cruyff no harm. Cruyff makes a picture, shows up at weddings and even reads poems on the radio. Where he used to open a shop for one hundred guilders and a meatball, Coster now calculates kilometers and hours. An hour of posing now quickly costs a thousand guilders. Most important of all: Coster forces a top contract for Cruyff at Ajax in no time: he will earn fifty thousand guilders a year, just as much as the new purchased star Dick van Dijk.

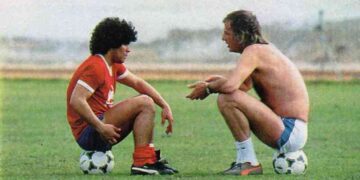

The shrewd businessman and the self-confident top football player have started something completely new: creating value around a sportsman and building wealth based on that. At the negotiating table, Coster and Cruyff grow into a formidable couple. Boundaries are sought, no means are left unused. In 1971, Coster agrees with Feyenoord on a multi-year contract, violating the gentlemen’s agreement between Ajax and Feyenoord, who promised not to take over any players from each other. Coster also threatens that Cruyff will leave for Mexico, where he can earn 700 thousand guilders per season. ‘Three years of playing football in South America and he doesn’t have to worry about the future anymore.’ The feints are mainly intended to put Ajax under pressure.

Finding the right sponsor

The trick with Puma is also pulled off again. In 1972, Coster was invited to the Adidas branch in Landersheim. CEO Horst Dassler receives him with a delicious dinner and expensive wine. When the thick cigars appear, Cruyff and Coster received a royal contract full of money. The Adidas boss does not even assume that he can buy the loyalty of the footballer, because Cruyff has been under contract with Puma since 1967. But, Dassler argues, he can at least push up the price and thereby weaken the hated competitor as much as possible. This is how it is done. With the Adidas offer in hand as a means of pressure, Cruyff signs a new contract with Puma that earns him 150 thousand guilders per year. That’s no less than six times as much as he realizes four years earlier through the famous lawsuit.

The successful negotiations with Puma not only earn Cruyff a princely compensation of 150 thousand guilders per year, but also form the prelude to a real riot. During the 1974 World Cup in Germany, the Dutch national team will be sponsored by Adidas, while Cruyff will tie his Pumas during the tournament.

The rivalling brothers Adolf and Rudolf Dassler founded the companies, both have their seat in the German village of Herzogenaurach and grew not only into global brands but also into each other’s biggest rivals. Neither of them wants the best footballer of that moment to advertise for the competitor. In the end, Cruyff puts an end to the discontent by playing the World Cup in the now famous shirt with the two stripes. What is also striking is the place where the caretaker puts his suitcase with adidas logo during Cruyff’s injury treatments. Right in front of the puma shoes of the star.

A revolutionary

What binds Cruyff and the revolutionaries is the means: revolting against the ruling authority. The sport was also run autocratically in those years. The power is up to the unions and the administrators. That regent society is a thorn in cruijff and Coster’s side. In 1969 Coster announced that he wanted to make contact with the VVCS, the Association for Contract Players, to advocate the end of the transfer system. ‘I sometimes want to test the transfer system for its legal feasibility’, says Coster, no less than 25 years before the introduction of the Bosman judgment. ‘Johan is Ajax’s servant, isn’t that how it is?’

Cruyff and Coster do not climb the barricades out of a lofty kind of idealism, but mainly out of self-interest. The top football player makes no secret of the fact that he wants to be financially independent at the age of 31. The reason is obvious: he says he is not good at anything apart from playing football.

With their rebellious attitude and far-reaching provocations, however, they also ensure an unmistakable emancipation in professional football. With Cruyff as a champion, the salaries of other players will also increase, they will also be asked for commercial projects from now on. In the negotiations with the KNVB, Coster and Cruyff forcefully that the internationals each receive a premium of 115 thousand guilders during the 1974 World Cup. The two also realize that from now on, not only the KNVB officials but also the internationals will travel well insured. ‘What do our women actually get when that box comes down?’, is Cruyff’s rhetorical question, with which he starts the negotiations with the KNVB.

Setting the example for years to come

Cruyff is indeed a revolutionary who creates a new, better reality. The many millionaires that today’s professional football spits out also owe their luxurious status partly to Cruyff’s actions. He said the following about this in VI in 2014: ‘The position of footballers has improved enormously. In the past, unions and administrators thought that they could abuse players morally and financially. Fortunately, that’s different now.’

Cruyff explains his own greed for money from the early death of his father Manus. Cruyff is twelve when his father dies because of a heart attack. As a result, the vegetable store ‘Cruyffs Potatoes’ cannot be continued and as the sole breadwinner, mother Nel goes to work as a housekeeper for Ajax coach Vic Buckingham. ‘After father’s death, our motto became: the strongest is he who has money. So make sure you are among the strongest’, Cruyff will explain later. He can understand that the term money wolf regularly falls in retrospect. “In essence, I was too. Because I didn’t have any money, but I wanted it.’

The early departure of father Cruyff causes another thing: Johan’s allergy to authority. As a player, coach and football philosopher, he will have numerous clashes with coaches, board members and dissenters in his career. ‘I was a quite a crosspatch’, he knows, ‘If I thought I had been treated unfairly, I became adrift because of built-up tensions and sometimes behaved like an unruly child.’ But it also helped him to become the great football star and total football philosopher as we remember him by.

Discover more from Barça Buzz

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.