When Johan Cruyff was born, every team played football with five strikers. In his youth he looked enthralled at The Dutch Golden Inner Trio. Abe Lenstra, Kees Rijvers and Faas Wilkes, the idol of Cruyff, were flanked in the Dutch national team by two wingers. Football was a hobby and attacking was the most fun.

By the time Cruyff made his debut in Ajax’s first team at the age of seventeen, those principles were in jeopardy. Football turned out to be business. That included a business-like style of play. These were the golden times of the Italian catenaccio. Helenio Herrera won the European Cup I with Internazionale in 1964 and 1965. According to the golden Herrera formula: Class + Preparation + Intelligence + Fitness = Championships.

This is Part 4 of #TheCruyffStory. Feel free to read Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3.

Catenaccio symbolized the worldview in which only profit counts and all means are justified to achieve that goal. Herrera canonized the counter as an offensive weapon. A quick attack is the best attack, was his conviction. By placing many people behind the ball defensively, Herrera hoped to entice the opponent to lose the organization, so that when winning the ball within three passes, the opponent’s penalty area could be reached. Dribbles and wide passes were therefore avoided as much as possible. ‘Because the ball always moves faster than the player behind it’, Herrera calculated.

Cynical calculation football replaced Real Madrid’s White Ballet from the fifties. As the famous Italian journalist Gianni Brera wrote: ‘The perfect match ends in 0-0.’ In that period of ultra defensive football, Cruyff took his first steps on the field. When Ajax lost 4-1 to AC Milan in the 1969 European Cup I final, the young attacker drew a harsh conclusion: ‘Ajax is still too sweet. Not so drilled and refined yet.’

Rinus Michels Found the Perfect Balance

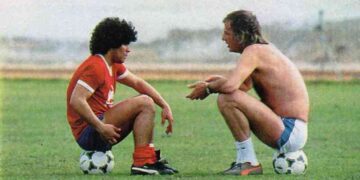

Rinus Michels had similar thoughts. “It obviously has to be harder,” said the trainer. But unlike his Italian colleagues, Michels did not give up his love for the ball. ‘We are looking for the balance between spectacle and certainty. That’s the hardest football there is.’ When Michels and Cruyff found that balance during the 1974 World Cup, the world was amazed.

With today’s knowledge, that Dutch team can be identified as the starting point of modern football. In which the best way of defending does not consist of hard mandekkers, but controlling possession in the enemy half and collectively chasing when losing the ball. In 2022 that is the norm, but in 1974 it was almost as if a team from the distant future had stepped out of a time machine. Orange set a pressing record in West Germany that will probably never be broken again.

This is shown by a statistic that is called passes per defensive action (PPDA). This is now used as a measure of the aggressiveness of a team’s pressure. The fewer passes allowed before an intervention follows, the more fanatical hunting is. Thanks to Opta Sports, these figures for historical tournaments are also transparent.

Total Football

The pressure that the Orange team developed in 1974 turns out to be so insane that opponents could not even successfully complete six passes in a row on average. At least as remarkable: in seven games, an opponent was sidelined 37 times. Because in Cruyff’s eyes, offside was not a defensive, but an offensive weapon. The average conquest of that Dutch team took place 42.7 meters from the own goal. Cruyff himself – the striker who was the first defender – took the most balls from the Dutch team that World Cup.

To put the PPDA of 5.7 in perspective, Liverpool’s pressing machine, which won the 2019/20 championship of England, came in at 8.0. At a final tournament, such a thing has never been seen again. Only the Netherlands itself came a bit close during the World Cup of 1978 (6.2) and 2006 (6.4). That team under national coach Ernst Happel built on the success of four years earlier. Cruyff was explicitly involved in that other team as an advisor to national coach Marco van Basten.

In the Orange of 1974, two tactical developments of the previous decade merged. That started with what Cruyff called Ajax’s ‘total football’. According to him, the core of this was simple: every player had an offensive and a defensive task. Now that sounds normal nowadays, but at the time this was a revolution. Because until that time, football consisted of attackers who wanted to create and defenders who wanted to prevent that. With sometimes a free defender behind the others to build in extra security.

Pressing as an Art

The second revolution was the introduction of pressing football. Cruyff: ‘Pressing is based on the principle that you try to contain the opponent and then also keep it locked up.’ Now it is customary to put pressure on the enemy half, but when the term pressing was coined by Cruyff, the norm was to sprint back forty meters when losing the ball.

‘In the seventies I have been connected as a coach with two constructive, attacking strategies that have left their mark on the evolution of the game of football: the so-called Total Football (Ajax 1970) and the attacking pressure football (Orange 1974)’, Michels noted about this development in his book Teambuilding. ‘Total football arose from my search for ways to break open the strengthened defences. That requires constructive and offensive actions with which you can surprise the opponent. That is why I opted for many position changes in and between the three lines. The main goal of the attacking pressure football, the hunting, was to regain possession as quickly as possible after losing the ball in an attack on the opponent’s half.’

Setting an example for many great coaches

In Italy, a young Arrigo Sacchi saw that even the image direction was unable to capture the Orange of 1974. “That team was a mystery to me,” said the later success coach of AC Milan. ‘The television was too small. It felt like I had to see the whole field to fully understand and appreciate what they were doing. That team was breathtaking.’ Or as Cruyff put it: ‘The football we played in the seventies was a controlled, controlled chaos.’

Even with his line-up, that Dutch team broke with all the prevailing conventions. An easy scoring midfielder with a lot of running ability was put in the middle of the back. As if Georginio Wijnaldum would happen now. So Arie Haan looked up strangely when Cruyff came to tell him that. “Are you crazy? I’m a midfielder, offensive midfielder still is. Is this a joke?’ It turned out not to be. Haan was given a quickcurcus positional defense by Cruyff. ‘Michels hardly spoke to me in those weeks. The one who talked to me a lot was Cruyff – in the field.’

With the same conviction, Cruyff went to war as a coach in the eighties and nineties against the convention that everything started with defensive qualities. For him, it was all about field occupation and mutual distances. Football was a game of spaces. For those who understood, it was simple. ‘Defending is not that difficult in itself, as long as you can limit the space you have to defend. With Barcelona we became champions with Ronald Koeman and Pep Guardiola in the centre. Those two couldn’t take a ball away from anyone, what are we talking about?’

Pep Guardiola as his best student

With that thought in mind, Guardiola became the most successful coach ever. That started when he was appointed at Barcelona in 2008 on the recommendation of Cruyff. “Our style is dictated by the history of the club and we will be faithful to it,” Guardiola placed himself in a tradition that he said consisted of maintaining the cathedral built by Cruyff in his first speech. “When we have the ball, we can’t lose it. When that does happen, we have to run and recapture him right away. That’s the basis.’

In his debut season at Premier League club Manchester City, Guardiola surprised the English press by asking the question what a tackle is. He constantly repeats that his players cannot defend and that possession is therefore the best protection against goals. “I sometimes ask my players: What is more dangerous, if the ball is close to our goal or far away from it? Of course the answer is: if he is close to our goal. Because then we are more likely to get a goal against. You don’t convince me of the opposite.’

In contrast to his teacher Cruyff – who worked purely on intuition – Guardiola interprets his working method in structure. He does this on the basis of the three P’s: positioning, possession and pressure. Positioning is about taking places on the field that allow for triangles and combinations. Possession to owning the ball. Pressure emphasizes the importance of direct pressure in case of ball loss. In Catalonia, this is called the three-second rule: whenever possible, Barcelona wants to have the ball back in possession within three seconds. At Vitesse, Peter Bosz later added two seconds: ‘Because we are less good than Barcelona.’

‘Cruyffismo’ – An Innovative approach for football

In 2017, Spanish scientist Claudio Alberto Casal found evidence for the views Cruyff passionately defended for decades. Successful teams appear to have the characteristic that they can keep possession of the ball for a long time in the opponent’s half. Bad teams play mainly around the own goal. That makes sense.

During the last Champions League final, the two teams that had the longest possession for a goal that tournament faced each other. At the Manchester City of Cruyff pupil Guardiola that was 15.6 seconds. Chelsea came under Thomas Tuchel to 14.9 seconds. The winning goal in the final started with goalkeeper Édouard Mendy, who under pressure found the free man in the build-up. Because as long as you have the ball, the other person can’t score.

Discover more from Barça Buzz

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.