“In a way, I’m probably immortal,” that’s how Johan Cruyff himself used to play football. And so, later as coach of Ajax and FC Barcelona, he also let his teams play football. Free and unsprung. Attacking and brutal. Seductive and provocative. Come on! As if death had to be more afraid of him than the other way around.

Johan Cruyff passed away on 24 March 2016. At the age of 68, lung cancer became fatal to him. Barcelona and the world were in shock, along Gaudí’s facades there were deep emotions. Spain had just celebrated Semana Santa, the holy week before Easter, and what followed was Johan Cruyff’s holy week. In newspapers and on TV, from banners and in shop windows; from all sides the dead star fluttered towards you. Letters and documentaries appeared, artists, star chefs and theatre directors brought odes, a newspaper handed out lollipops and special T-shirts came on the market. Cruyff depicted on the chest as Fifth Beatle? It was all possible.

Cruyff received the impressive farewell that belongs to dead kings and disembodied presidents. No less than sixty thousand mourners passed by the memorial that FC Barcelona had set up for him in Camp Nou. Joan Laporta, now again the president of FC Barcelona, praised Cruyff as a revolutionary and a universal genius. ‘Johan made you believe that you can win anything, as long as you strive for excellence. We now prefer to be the best instead of the first. We want to win 6-5 instead of 1-0.’

Florentino Pérez, still president of Real Madrid, kept it a little simpler. ‘For me, Cruyff was one of the people who should never die.’

This is Part 13 of #TheCruyffStory. You can read the whole series here.

Even in the enemy’s camp, Cruyff was openly mourned. The maestro himself would have found it only logical. After all, he had made FC Barcelona great, first as a player and later as a coach. And as a result, Cruyff had also made the great Real Madrid even bigger. And by extension, the mutual matches and thus the allure of the Spanish league. Matches between Barcelona and Real Madrid used to be called El Clásico. Today they are called The Classic of the Universe. As if there is nothing else up there.

To understand some of these heavy sentiments, we have to go back half a century in time. When Johan Cruyff was bought by Barcelona from Ajax on August 24, 1973, Spain suffered under the fascist rule of General Franco. Especially the region of Catalonia, yearning for independence, was oppressed by the dictator. The use of the Catalan flag La Senyera was forbidden, Catalan politicians, artists and writers were banned and speaking the Catalan language was even punishable by imprisonment.

The Dark Franco Era

In those dark days, Futbol Club Barcelona was one of the few ways for the enslaved and silenced Catalans to show their own identity. In the stadium, they could at least raise their voices and oppose. Even when it came to football, the Catalan felt subjugated by Madrid, especially since Franco had proclaimed Real Madrid by decree as Spain’s chief ambassador to the rest of the world.

Since then, FC Barcelona has felt that they are systematically disadvantaged by everything that is based in Madrid; whether it is the football association, the government or the referee organization. In the capital of Catalonia, reference is still made to the extremely curious chicane with Alfredo Di Stéfano. In 1953, the wonder dribbler from Argentina already wore the Barcelona shirt for a presentation. But under pressure from the regime in Madrid, his Colombian club Millonarios did not sell him to Barcelona, but to Real Madrid. With Di Stéfano in the team, Real Madrid then won the European Cup for national champions five years in a row.

Without star player Di Stéfano, Barcelona turned into a club that was suffering heavily in the early seventies. Also in a sporting sense. The last championship dated from 1960, the team played unattractive football, the game was usually gravelly.

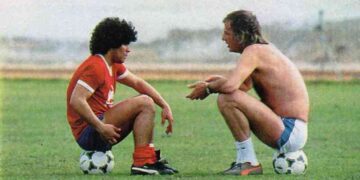

And then came Cruyff. Or rather: he appeared.

The Dutchman was the conductor of the unapproachable Ajax that had won the European Cup for Champions (now UCL) in the three previous seasons. He was generally regarded as the best footballer in the world and was at least the most expensive at that time with a transfer fee of three million guilders. Yet there were doubts among the culés, the fans of Barcelona, as evidenced by the later documentary En Un Momento Dado. When Cruyff arrived, the tenor was: ‘Should this skinny, shrill man who also smokes like a heretic, save us?’

So, yes.

Also because Cruyff himself had no doubts at Barcelona. In 1971 he had already turned down a regal offer from Real Madrid. For him, there was only one club in Spain, although he has never been able to explain exactly why. Maybe it was that name, which rustled softly like a sound of love. Bar-se-lóna. In the past, as a little boy, he searched the newspapers for results and stories about FC Barcelona. With Glasgow Rangers in Scotland and FC Servette in Switzerland he had the same. What also played a role: as a fan and champion of his own rights, Cruyff had always thought it was unjustified that Di Stéfano, who had chosen Barcelona of his own free will, had been coldly claimed by Real Madrid.

It only took a moment before the Catalans pressed El Flaco to the chest, as they soon affectionately called him. The Skinny. Just like before at Ajax, Cruyff also proved to be a brilliant conductor of success and glory in Barcelona. After he had made his debut on the eighth matchday in October 1973, Rinus Michels’ team remained no less than 24 league games without defeat. From the seventeenth place in mid-October it went in one impressive march to the championship, the first title since 1960. What was at least as important: Johan Cruyff played football the way the Catalan wanted to be. Perky, upright in the wind, sovereignly ruling over man and ball, free-spirited especially.

And then it was February 17, 1974. Day of the immortals, as it turned out later.

For Barcelona, the fraught trip to Madrid was on the program. The match was also important for Cruyff. His wife Danny was heavily pregnant and pretty much on the date of the Clásico. At Michels’ instigation, the couple therefore decided to give birth to their third child early with a caesarean section in hospital.

Jordi Cruyff was born on February 9, 1974, and the Catalans loved it, because Jordi is the name of their patron saint. Eight days later, the myth of the footballer Cruyff becoming a saviour was born, and the Catalans loved it again. Almost single-handedly, Cruyff silenced Bernabéu. He swirled around the pitch for ninety minutes, scoring one goal, preparing two and leading Barcelona to a historic 5-0 victory.

It seemed like an extraterrestrial celebration that Cruyff unleashed in Barcelona. On the Plaça de Catalunya the bonfires flared and the touched culés fell into each other’s arms crying. Finally, they felt freed from Madrid. Even if it was only for a while and even if it was only through football and therefore mainly symbolic. But the symbolism did have primal power in it. After all, the hated hereditary enemy had been humiliated from a football technical point of view, in the tyrant’s own house, and moreover Franco was dying.

Therefore, many Catalans still argue, on that February day in 1974, the final decline of the dictatorship was set in motion and the rebirth of FC Barcelona began. Even The New York Times, certainly not a newspaper that followed football closely, wrote about it. “Johan Cruyff has done more for the interests of the Catalan people in one day than all the politicians in the previous decades combined.”

A hero the Catalans needed, on and off the field

The footballer, celebrated as a modern fairytale character, hardly realized which sensations he unleashed in Catalonia. Of course, he was aware in 1973 that he would play under Franco’s dictatorship, but he did not know much about the complex undercurrents of the Catalan question. The naming of son Jordi, for example, was based on more innocence than intent.

Only when Cruyff reported to the birth register in Barcelona did he learn that the first name Jordi had been banned by Franco because it was the name of the patron saint of Catalonia. Call him Jorge, the official said benevolently. But Cruyff and Danny simply thought Jordi was a nice name. In Cruyff’s world of experience, there was a solution to every problem and that is why he went to Amsterdam. After all, Jordi came into the world there by caesarean section and there he instantly becam an official resident of Barcelona. The first and only Jordi during Franco’s reign. “Since then I became even more popular with the Catalans, but that was really not my intention,” Cruyff once said. ‘Sometimes you’re lucky.’

Two decades later, Cruyff finally completed his own glory, this time as a coach. At Camp Nou he was the creator of the Dream Team, with players like Michael Laudrup, Ronald Koeman, Pep Guardiola, Hristo Stoichkov and later Romário, which combined attractive football with success and even got something of an elusive magic over it. After all, three of the four championships that Barcelona won between 1991 and 1994 came about on the last matchday of the competition, always because the competition committed an unthinkable misstep.

Dramatic titles

Cruyff also experienced the day of the immortals as a coach. On May 20, 1992, the coach finally relieved Barcelona of its inferiority complex. At Wembley, the club captured the first European Cup for Champions against Sampdoria, thanks to a freekick goal of Cruyff’s compatriot Ronald Koeman. Finally! Real Madrid already had six in the trophy cabinet at that time. The miracle went far beyond that one bang from Koeman. At Wembley, the birth of the modern FC Barcelona was announced. Because it is mainly the important prizes that transform a big club into a world club.

It is because of these kinds of major events that Cruyff was soon called El Salvador in the Netherlands. The Redeemer. The nickname came from a Dutch journalist and such terminology was never used by the Catalans themselves.

Bottom line

In a metaphorical sense, the people in Cruyff who yearn for independence did indeed discover the personification of the independence fighter. An undisputed leader, with far too long hair, an adventurous and elegant style and a rebellious character. The footballer Cruyff was already averse to conventions and fear of authorities and the coach Cruyff manifested himself as an autonomous and often transverse thinker. A life artist, like Joan Laporta said at his farewell, ‘who taught us again to live courageously’.

That spirit can still be seen in the annual demonstrations for independence of Catalonia. On 11 September 2021, 400,000 people gathered in Barcelona. Cruyff’s spirit also lives on in other ways. Barcelona named the stadium for youth after him and in Amsterdam The Arena was renamed to Johan Cruyff Arena. Coaches such as Arrigo Sacchi, Louis van Gaal, Pep Guardiola, Jürgen Klopp, Ralf Rangnick, Hansi Flick, Erik ten Hag and Roberto Martínez have been influenced to a greater or lesser extent by his football philosophy, and in turn passed those ideas on to the next generation of coaches, such as Xavi, the current coach of Barça. Artists, writers and politicians are also still inspired by his creativity and original way of thinking.

Johan Cruyff has thus become above all a style icon, an influencer avant-la-lettre, whose words still have great expressiveness and whose convictions live on forever.

In that sense, he is certainly immortal.

He was right again.

Discover more from Barça Buzz

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.