Before Cruyff, It was the time of Denis Law, the agile Scotsman who scored 237 for Manchester United. The time of Gigi Riva’s golden left foot, who ran almost one-on-one in the Italian national team for a decade. It was the time of Gerd Müller, Der Bomber, who only lived for the next goal and eventually scored more than five hundred times for Bayern Munich.

Late sixties, early seventies; it was the heyday of the goaltender. The striker for whom task one, two and three was scoring. The Netherlands also had its Bombers. Think of Dick van Dijk, Ruud Geels and of course the eternal Eredivisie top scorer Willy van der Kuijlen. Gentlemen who were born with a nose for the goal.

This is Part 11 of #TheCruyffStory.

There was no great variation in striker country. You had the fast type, which had to be launched at full sprint speed behind the defensive line. You had the type with a devastating shot in the legs. And you had the strong target man, the reliable end point for the many crosses from the flanks. Ideally, a striker possessed all those qualities. But above all: a striker was as close as possible to the box and was judged on his goals.

It makes Johan Cruyff’s dominance in exactly the same period all the more special. Admittedly, Cruyff of course also just strung together the goals. Between 1966 and 1972, an average year ended for him with 33 goals. But even bigger was his impact on the positional play of Ajax and the Dutch national team. Cruyff was the striker who could never be found in the box…

Johan Cruyff leaded the attack, the one who allowed his teammates to flourish in the spaces from which he left. The two-legged dribble king who was everywhere, the playmaker in the tip. The original false number 9. Or, as Cruyff himself called it, ‘the footballing mid-forward’.

Not the Clasic Striker

Cruyff’s qualities as a roaming mid-forward played a key role in total football in the seventies. Ajax and the Dutch team drove opponents crazy, because each field player could swap positions with someone else at any time. Emerging backs, slumping wingers, deep mid mids; it was all possible.

Finding the open space was sacred. Not the allocated places on the setup board. And it all started with Cruyff’s role. The world’s best playmaker at the time, the best dribbler, started up front, but rarely stayed there. Cruyff roamed where he was needed. Where he could control the game. Or, in his Cruyffian language: ‘A bit of wandering, a bit of football and, if the situation called for it, making the action.’

Free-Role Positions

Looking back at Ajax’s positional play in those European Cup tournaments and the Dutch team at the 1974 World Cup has almost something unreal. Opponents had little idea what was happening to them. Defenders followed Cruyff all over the field, leaving huge holes in their own defence. Or they let Cruyff go after a few such misunderstandings, which was also not a good idea against someone with such qualities in the one-on-one.

Cruyff’s teams dominated with their possession. Almost continuously there was as superior number of available players around the ball. Ajax and the Dutch team dominated completely in the middle zone, which is now so sacred in modern football tactics. Cruyff’s interaction with Johnny Rep, Rob Rensenbrink and Johan Neeskens was phenomenal at the World Cup in West Germany. Time and time again, one of these three was released into the spaces that Cruyff had just left. Time and time again, the Orange team played its way to free space with triangle combinations.

Cruyff explained it in detail in 1977. ‘The special thing about the Dutch national team’, he said, ‘is that everyone moves. So that’s the basis. If at some point you say: Cruyff drops back a lot, he can play better in midfield, then you are already wrong, then you have not understood anything. Because you can only rotate if one position is not occupied. That is the mid-front position, so it is not occupied. Then defenders of our opponent have problems, because then one comes in from the right, then one from the left, from all sides they come through the center, and the defenders have to chose. Plus, if they don’t follow me, I’m free. When I’m free, it gets even easier. If they follow me, they will miss a player in the defense.’

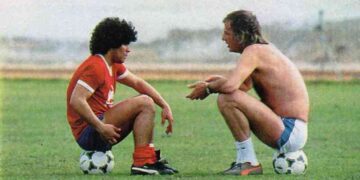

As a coach

It was precisely by deviating from the norm that Cruyff achieved his greatest successes as a player. Where the striker position, if it was traditionally filled, at that time had perhaps the simplest tactical tasks of all field players (go deep, win aerial duels and above all: score), Cruyff perfected his game in a very complex role. A role of false 9 that is completely focused on the interplay and the cohesion with the players around him.

This false-striker role was too complex, too risky for many coaches and players. Because when Cruyff returned to Barcelona as a coach in 1988, this tactical variant had been somewhat forgotten. Not for long. Because the Dream Team that Cruyff eventually put together, often housed such a type of striker.

At his entrance in Catalonia in the summer of 1989, Michael Laudrup was considered one of the most beautiful stylists in the world who did not want to flourish in Italy. A reputation that the Dane had amassed as a left winger and number 10. Nevertheless, Cruyff did not hesitate to transfer Laudrup to Barcelona. Hristo Stoichkov, for years a goal-scoring machine at CSKA Sofia, reported to Camp Nou a year later and had to give way to the flank.

‘Triangles’ – The essence of the Cruyffismo

As a tactician, Cruyff was obsessed with creating triangles in positional play. And with libero Ronald Koeman, controller Pep Guardiola, attacking midfielder José María Bakero and false striker Laudrup, Cruyff’s 3-4-3 diamond had a four-man axis of players who could keep fitting themselves out of almost any predicament. Barcelona’s Dream Team has a lot of overlap in terms of playing patterns with the tiqui-taca that decades later became art in Guardiola’s Barcelona and the dominant national team of Spain.

Where Cruyff’s choice of Laudrup as a false 9 already resulted in brilliant football at Camp Nou, it was Guardiola who let the best player of all time tap a new level as a false striker.

Leo Messi as a False 9

The birthday of the superstar of superstars is May 2, 2009. Messi was already the world’s most intriguing talent and Barcelona already very good. But on that day, both of their levels rose even further.

In the first season under coach Pep Guardiola, Barcelona was four points ahead of archrival Real Madrid, when on matchday 34 the next Clásico presented itself at the Estadio Bernabéu. The pressure on Guardiola was great: Barcelona had already missed out on the league title two seasons in a row and due to a 2-2 at Valencia on the matchday before, he suddenly felt the hot breath from Madrid in the neck. At that moment, Guardiola could not suppress his inner Cruyff.

The ‘Talk’

So he called Messi on the night before the game. He needed to come by. At about half past eleven Guardiola heard a cautious knock on the door of his office. Martí Perarnau, author of bestseller Pep Confidential, described what happened next:

“The 21-year-old Leo Messi comes in. Guardiola shows him the video he wanted to discuss, puts the image on hold and points to the empty space that has been created. He wants his player to make that space his own. From that moment on, it will be the Messi zone. “Tomorrow in Madrid I want you to start in your familiar place on the sidelines,” Guardiola said. “But if I give you a sign, I want you to move to the place I just showed you. The moment Xavi or Iniesta break through the lines and give you the ball, I want you to go straight for Iker Casillas’ goal.”

‘For a long time, it remained a well-kept secret between the two. Nobody knew anything about the plans, until Pep told his assistant Tito Vilanova about it the next day in the players’ hotel. Just a few minutes before kick-off, Guardiola called Xavi and Iniesta to him and also informed them.

It turned out to be a golden opportunity. What followed was a historic football show in the Spanish capital. Samuel Eto’o, La Liga’s top scorer with 27 goals, suddenly popped up on the right. Messi, who was up front against the sharp, hard-hitting, but old Real defence. And tehn disappeared and left the space open. Like Cruyff, the Argentine ruled. Barcelona triumphed 2-6.

Unforgettible match

Xavi will never forget that match. “Guardiola had changed the whole match plan,” the current coach of Barcelona once told La Vanguardia. ‘With Messi as a false 9 and with Henry and Eto’o in between the central defenders and backs of the opponent. Right in those free spaces. This allowed Leo, Andrés and I to dominate centrally on the field.’

“We got man coverage from Fernando Gago and Lassana Diarra,” Xavi remembered, “while Messi dropped back. Their central defenders Fabio Cannavaro and Christoph Metzelder did not follow him, so the three of us always had an extra player in the middle. Pep watched and it actually went perfectly. It was a historical dominance. After the game we went to the dressing room and a party arose spontaneously. High fives, hugs, screams… That victory brought us closer to the title. It was without a doubt one of the best games of my career.’

Barcelona would also win the Copa del Rey a week and a half later, win La Liga title the following weekend and finally crown the season with the Champions League win. In that final against Manchester United, Guardiola repeated his trick. He started with Eto’o in the point and exchanged him with Messi after about ten minutes. He decided the final as a striker with a magnificent header.

For example, the 2-6 in Madrid was the resurrection of miracle striker Messi. After that, he would score at least forty goals for Barcelona for ten (!) seasons in a row. A strength that the little Argentinian, just like Cruyff, combined with solos and smart passes, with which he helped shape the positional play.

Thanks to the triangles and spaces created by Messi all over the pitch.

For a long time, the idea of the false 9 was largely ignored in the rest of the football world. But that has changed. A look at European football in 2022 shows that the top teams that are most successful with spectacular, attacking play, usually operate without a static centre forward. The footballing mid-forward has almost become the standard in the best club competition in the world, the Premier League.

At Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool, the number 9 mainly plays in the service of the two wingers, his absolute star players Sadio Mané and Mo Salah. Chelsea paid more than a hundred million euros down for Romelu Lukaku, but in crucial matches Thomas Tuchel mostly uses a false striker, playing Kai Havertz. With Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City, the whole idea has evolved a step further.

The almost always dominating Citizens can also just play with two false 9’s. In those games, Guardiola opts for two attacking midfielders – for example Kevin De Bruyne and Bernardo Silva – who take turns strengthening the midfield from the striker. That way of playing lends itself to even more variation and position changes. Like Liverpool, Manchester City don’t even have a single traditional striker in the squad.

Bottom Line

Once again, Cruyff was far, far ahead of his time. In the seventies he was unique with his interpretation of the striker position. Now every top club is looking for its own Cruyff. Because a striker is much more than a goalscorer. By leaving that position vacant, the dynamic that is more important than ever against well-organized defenses, begins.

Discover more from Barça Buzz

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.