Johan Cruyff once drafted a goalkeeper without hands. This Carles Busquets – Sergio’s father – could be recognized by an old-fashioned training pants and preferred to stop balls with his feet. The newspapers therefore called him El Portero sin Manos, the goalkeeper without hands.

Nevertheless, Cruyff claimed, pointing to the low number of goals conceded in the 1995/96 season, that El Portero sin Manos was one of the most effective closing posts in Barcelona’s recent history. Others saw blunders, Cruyff saw someone without fear. With that, Busquets fitted into his ideal. He wanted an eleventh field player who happened to have gloves on. Cruyff even openly flirted with the idea of having a defender put on the goalkeeper’s jersey. Assistants Charly Rexach and Tonny Bruins Slot talked that idea out of his head.

This is Part 10 of #TheCruyffStory series.

The choice of Busquets, who was partly trained as a striker, was a compromise. The outside world thought Cruyff was crazy. With Andoni Zubizarreta, he had what was considered the ideal goalkeeper at the time: big, strong and capable of heroic saves on the line. The 126-time international of Spain was perfectly described when Ruud Gullit stated that ‘a goalkeeper is a goalkeeper because he cannot play football’.

To Zubizarreta’s annoyance, Cruyff told anyone who wanted to hear it – including the press – that it was not he but Stanley Menzo from Ajax who was the best goalkeeper in the world. To make matters worse, he had to use his feet more and more often during training sessions. ‘When Johan put the goalkeepers in the rondo in the preparation, I thought he usually did it to humiliate and tease me.’ In the exercises that the then Spanish record international saw as a personal feud, a fundamental difference in vision of the goalkeeping profession actually revealed itself. Cruyff’s ideal goalkeeper didn’t really need gloves.

Goalkeeper as a Sweeper

For Cruyff, a team did not consist of ten players and a goalkeeper, but eleven players, one of whom happened to occasionally use his hands. This number 1 was part of the whole, instead of an isolated loner.

‘Total football has everything to do with the distances on the field and between the lines. When you play football like that, even the goalkeeper counts as one line’, he explained in his book Cruyff Voetbal. ‘Since the goalkeeper is no longer allowed to pick up a replay ball, he must also be able to play football. Someone who is ready to participate when the defender has the ball.

Often positioned on the edge of the penalty area, in order to be playable for fellow players. That is why there was no place for a line keeper in our way of playing at the World Cup in Germany. The nice thing was that Jan Jongbloed had been a striker in his youth. As a goalkeeper, he not only liked to play football, but he could also do it very well and often prevented goals because he was able to think as an attacker.’

Sometimes it doesn’t work

Some people claim that the drafting of Jongbloed during the 1974 World Cup has costed the Netherlands the world title. Books have been written about the conflict between Cruyff and Jan van Beveren, who was clearly superior to Jongbloed in the traditional work of a goalkeeper. Just like Carles Busquets, Jongbloed did not like diving.

The goals conceded by Paul Breitner and Gerd Müller in the final against West Germany were charged to him because he didn’t even seem to make an attempt to save. Earlier that tournament, according to the diary of Jongbloed published by Vrij Nederland magazine, this already caused irritation. ‘I trained with Van der Hart (then assistant, ed.), who always let me do exercises where I have to dive’, wrote the man who wore number 8 at the time. “However, this is difficult for me. I don’t dive when I can walk it. I can’t bring him to his senses.’

Van Beveren was the opposite. He preferred to dive gracefully to the corner as often as possible. Cruyff called him ‘a good goalkeeper, but also a fearful goalkeeper’. Although the outside world did not seem to believe any of this, Cruyff persisted even in his posthumously published biography in the position that the passing of Van Beveren was purely based on sporting arguments. As with Busquets, Jongbloed’s stats were better than his reputation. In eight of his twelve matches at a final tournament, he did not conceive a goal against. His rescue rate of 76 percent was also above average.

The Choice of Menzo

The glasses through which Cruyff looked at goalkeepers were so different that dark conspiracies were constantly suspected. That became clear again in the eighties. Cruyff passionately pleaded for Menzo as a goalie for the Dutch national team. Even after Hans van Breukelen, who was clearly better than his competitor with his hands, had played a major role in winning the European Championship title in 1988 with a stopped penalty kick. For Cruyff, that hardly seemed to matter. He was loyal to the man who, during his time as Ajax coach, was willing to go along with his radical views on the profession of goalkeeper.

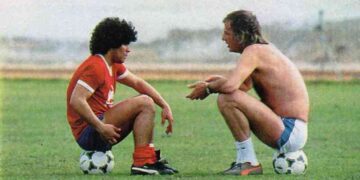

This would have been more difficult for Piet Schrijvers in 1979. When Cruyff arrived as a technical advisor, De Beer van De Meer was immediately in his office. ‘We play attacking football with Ajax, then you shouldn’t stay on the goal line, but choose a position near the sixteen-meter line’, Cruyff told him. “Then you have to constantly give directions and you will have to bring salvation once or six or seven times via rapid run-out. Moreover, practice shows that the biggest fear of a goalkeeper, that he will be passed by a curve ball from the middle line, is based on nothing.’

A Change takes time

For the then already 33-year-old Schrijvers, who had to sit on the bench at two World Cups behind the better footballing Jongbloed, changing his style proved difficult. Like many goalkeepers, he loved the comfort of the goal line. That’s why Cruyff liked Menzo so much. He dared to carry out what Cruyff told him to do. Even after that had gone wrong a number of times with goals against and ridicule as a result. “I think I was the type of goalkeeper you see a lot these days,” Menzo said. ‘Sometimes I had to stand thirty or forty meters in front of my goal. I did what Cruyff asked of me, but that was not so special for me, because I always played like that. For me, his style of play was very normal.’

To help Menzo, Cruyff invented the function of goalkeeper trainer. He read a book by Frans Hoek, at the time still an active goalkeeper for FC Volendam, which pleased him so much that he brought him in. At that time, Hoek had never given a training. Moreover, no one in the world had yet come up with the idea of having a specialist work with goalkeepers. For Cruyff, that turned out to be no objection. Hoek even got the entire selection at his disposal on Thursdays, so that Menzo could practice in a match-real situation to play the spaces behind the defense.

1990 and the GK rule

Cruyff directed this revolution under the bar at a time when goalkeepers were still allowed to pick up replay balls. That undermined the importance of playing football. In fact, passes to the back were emphatically used as a defensive tactic. The 1990 World Cup proved to be the absolute low point. During the last group game against Egypt, Irish goalkeeper Pat Bonner kept possession of the ball for a total of six minutes by walking back and forth in his own sixteen. During Denmark’s European Championship win, Peter Schmeichel applied similar tricks two years later.

FIFA had already decided on a rule change. After a pass back with the feet, goalkeepers were no longer allowed to pick up the ball. This accelerated the transformation that Cruyff had been trying to set in motion for twenty years. Suddenly, the footwork of goal players became crucial.

‘That was a problem for the whole world, except for Ajax’, Hoek recently looked back on that historic moment. ‘Also because Louis van Gaal had a very far-sighted view and vision, so that the situation became an advantage. If the goalkeeper of the opponent got the ball, we put pressure and we had it in possession, while we could just play our goalkeepers ourselves. We had Menzo and later Van der Sar, who mastered spaces and football very well. Cruyff had started that, by thinking out of the box.’

What once was an innovation is now basic for Goalkeepers

Nowadays, giving passes is by far the most important part of the modern goalkeeping profession. Whether it is the Champions League, Eredivisie or Premier League: actions of goalkeepers can be roughly classified as follows: Almost eighty percent of the work on the ball involves giving passes. Saves only account for seven percent of a goalkeeper’s total number of ball contacts.

The better the team, the more emphasis will be on playing football. At top clubs, rescues often involve less than five percent of the actions. There is a double cause for this. First of all, these types of goalkeepers simply have to deal with fewer balls between the posts. Secondly, they are more often involved in the build-up, because their team generally has a lot of possession.

During the 2014 World Cup, Manuel Neuer showed the world the usefulness of the libero goalkeeper. The German goalkeeper played football at Bayern Munich at the time under Cruyff’s heir Pep Guardiola. He asked him to play extremely far forward and he translated that style to the national team.

“He didn’t have to do much on the goal line, but showed how important he is for his goal,” Joachim Löw said after the victory over Algeria in the eighth final. With that, the national coach did not say a word too much. Neuer recorded 59 ball contacts that match, of which no less than 19 outside the penalty area. Only three times did he need to make a save.

This goalkeeper without hands was not criticized, but showered with praise. The ultimate confirmation that forty years after Jan Jongbloed and twenty years after Carles Busquets, the vision of the role of a goalkeeper has completely changed. Thanks to the pioneer Johan Cruyff.

Discover more from Barça Buzz

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.